City diary

‘The online exhibition Corona in the City is like a bucket of pond water: the murkiness of the corona year turns out to be teeming with life.’ Read here the essay by Roos van der Lint about Corona in the City.

A stood alongside the Amstel River and looked around, but no one looked at it in return. And it wasn’t the only blue pepper grinder in town: there are dozens of such transformer booths, usually pasted on all sides with posters announcing cultural events, but in this year of corona, they remained a solid blue. They stood in their familiar positions, scattered around the various city neighbourhoods, at busy intersections and in quiet parks, next to a playground in Nieuw-West, on the riverbank by the Walter Süskind bridge and on the quay of Scheepstimmermanstraat in the eastern docks area. On summer days their blue merged with the blue of the sky and the water, and in the winter they struck a bright contrast with the snow.

A clandestine poster appeared on the booth by Wertheimpark – ‘Ik geef een nier voor geen Mark Rutte IV’ (roughly: ‘I would give a leg to boot the prime minister out of office’) – but most remained empty and silent, for lack of any events to announce. They reminded me of the television test images of old, waiting for a broadcast to begin, and in the meantime emanating a kind of visual fuzz that would annoy any TV watcher today, but that passers-by barely seemed to notice now.

Blue pepper grinder Wertheimpark, by Huub Zeeman

Silence and emptiness became the buzzwords of the past corona year. They described the most striking changes following the first lockdown, at least in the city: deserted streets and empty squares, shuttered cafés and restaurants and dead quiet evenings. They are also perhaps the most frequently used terms in the titles and descriptions of the displays (read: the digital files) in the galleries (read: the website pages) of the online exhibition Corona in the City – an initiative by the Amsterdam Museum in collaboration with a range of city partners. The museum called on fellow city residents to submit some sort of testimony regarding their experience of the pandemic, and the response was overwhelming. The new regime of strict order, so at odds with the freewheeling city life, and all the problems and feelings that this caused, stimulated residents and visitors to document their experiences and reflections in the form of stories and drawings, photographs and videos, spoken messages and all sorts of digital items.

Indeed, the yield of one year of Corona in the City is largely inspired by seeing the empty streets and squares and feeling the silence and loneliness at home. The exhibition includes a number of galleries devoted specifically to these themes, such as the one titled ‘The Silent City’, and there’s even a gallery that consists wholly of photographs of Dam Square. Yet at the same time, all the contributions put together – and at this moment of writing there are more than 2800 contributions – contradict the notion of emptiness. Clearly, the city continued to exist during the corona pandemic, and although there were hardly any people to be seen on the streets, they were clearly alive and kicking elsewhere.

Breath-taking silence, by Ruben Hanssen

Corona in the City is like a bucket of pond water: the murkiness of the corona year turns out to be teeming with life. It took just a squint of the eye to see how the city became the backdrop to a continuous interplay between emptiness and fullness, between visibility and invisibility. Most of the contributions to the exhibition relate to this theme. One citizen, Marie Anne Remmelink, was struck by the sight of a solid blue pepper grinder, and posted a call on Facebook for fellow citizens to document them all. It became a photo series and even a gallery of Corona in the City. Remmelink’s accompanying comment reads: ‘There was nothing to do in the city in the winter and spring of 2021. But on the other hand there was. Suddenly, a whole group of people started staring at nothing. It was addictive.’

***

Often something new emerged to replace that nothing. For instance the #HoeGaatHetEchtMetJe initiative, taking the form of posters pasted on street electrical cabinets. These didn’t announce a cultural event, but did enable citizens to share their thoughts and experiences. Launched by Merel Noorlander and Arthur Kneepkens, in collaboration with Framer Framed, community artists engaged neighbourhood residents in conversation, ranging from high school students in Zuid to senior citizens in Noord and to sex workers in the red light district. Quotes from these conversations were spread around the city, thereby opening up new worlds that extended far beyond the limits of the city, or instead probed deeply within for a profound sense of human nature. ‘So here I am now, as a sex worker without financial support and as a black transperson facing passport checks and racism on the streets’, reported one person anonymously. And a random passer-by on Krugerplein said, ‘I feel like an alarm for other people’.

The particular strength of Corona in the City is how it offers a platform for the mundane. Search on the internet for ‘corona in the city’, and you are immediately presented all sorts of graphs showing statistics based on the latest figures and recently compiled averages. The exhibition under the same title offers an important counterweight to an era ruled by numbers. Corona in the City unites the city with its citizens in a new way, and the many thousands of idiosyncratic impressions gathered on the online platform will automatically be added to the Amsterdam Museum’s collection. It is the place that everyone with an internet connection can visit and can contribute to, also during lockdown, and it’s entirely free, too.

Clicking and scrolling through the galleries – which are partly filled by the museum and partly by partners, including De Groene Amsterdammer) – takes you from the poignant to the sentimental, from the obscure to the obscene, from stone cold reality to poetry. From a street organ grinder with his coin box attached to a 1.5 metre pole, you jump to a piano piece that promises ‘light at the end of the tunnel’, and from a young man rummaging through his kitchen cupboards to a performance of nude people waving their legs in the air, and from a photo series made by an IC nurse to a sketch of a waffle vendor waiting for customers.

‘Waffle vendor waiting for customers’ by Mathilde muPe.

‘Waffle vendor waiting for customers’ by Mathilde muPe.

It isn’t quite accurate to describe Corona in the City as an exhibition, however, at least not in the classic sense of the word, but also not really as an online variant. As a whole it lacks a particular focus, or a critical selection by an institution wishing to communicate a message. The differences in terms of genre and the quality of the contributions are too big. The website is of course still under development and a new gallery opens every week, but it remains a random affair that is impossible to navigate properly: even online, fifty galleries are simply too much to take in, also with the awareness that there’s always more to come.

But it would also not do justice to the underlying ambition to treat Corona in the City as an exhibition. For we must ask, how do we want to remember this corona pandemic year, which was so radically different from all preceding years, in the future? What do we wish to save or preserve, and what can we let go and forget? Or, perhaps better said: what do we need to be able to recount the story of how the pandemic affected our lives? It’s the type of question we ask and answer at a personal level every day, for instance when deciding what to jot down in our diary, or whether to save the red polling station pencil or to throw it in the bin. But who makes these choices for the city as a whole?

A dime for the organ grinder, by Suzanne Bunnik

Immediately after the first outbreak of the virus, museums all around the world started collecting. The Museum of London launched Collecting Corona, a so-called ‘rapid response collecting’ programme aimed at collecting objects at the instant of a major event. Londoners could contribute both objects and experiences, and the museum gratefully accepted all, even including city residents’ night-time dreams. The Museum of the City of New York did something similar and subsequently compiled an exhibition based on the tens of thousands of submissions: New York Responds: The First Six Months. It includes an emergency ventilator that medical staff of the Mount Sinai Hospital fabricated for COVID patients using devices designed to counter sleep apnoea.

The Amsterdam Museum also added some corona-related objects to its collection, such as the first vaccination syringe issued to a nurse at the vaccination facility in Amsterdam’s RAI convention centre. However mundane, such items are hugely evocative. They testify to a moment in time that we, as spectators, can never return to, and the significance of which will continue to evolve and expand over time. As an exhibition display, visitors will certainly take a close look at this syringe, and even more so one hundred years from now. The less tangible stories that belong to an era form a different type of material: lived reality tends to slip through our fingers and scatter like dust, before we know it.

Transfer, by Kim Marquardt

***

Corona in the City is part of the project Collecting the City in the runup to celebrating Amsterdam’s 750th anniversary in 2025. Working with various partner organisations, the Amsterdam Museum wants to collect ‘the city’ and to that end is explicitly inviting everyone to contribute stories. This fits the current time of course, as museums no longer wish to simply present a single dominant story. As an example, see how the slavery exhibition in the Rijksmuseum presents this complex history from the perspectives of ten historical protagonists. It also fits with today, since there are no limits to an online platform, so that there is literally infinite space to accommodate all those stories.

For the first time ever, there is also the idea that things stored online can be preserved for ever. Until now, by far the greater part of history was irretrievably lost, which is both a blessing and a curse. It is a blessing for historians and artists who are eager to explore scarce materials and whose job it is to give meaning to what we have lost. But it is a curse for the ingrained power systems whose effect it is to invest the preserved archives, and all the historical reconstructions made on that basis, with a very particular bias.

In the podcast series, The Plantation of our Ancestors, Maartje Duin discovers that at the time of the abolishment of slavery in 1863, her great-great-grandmother co-owned a sugar plantation in Suriname (at the time a Dutch colony). She sets out to find descendants of the freed slaves and continues her quest with one of them, Peggy Bouva. Bouva cannot pursue her investigation as rigorously as Duin – after all, not much history was preserved for enslaved people.

Personal stories are the lubricant of history, and the rare pieces that offer a direct window on daily life in long-ago eras are the gems of our historical collections. It therefore sounds like a perfect scenario to preserve today’s daily life in full and forever. Or does this reveal an overly optimistic view of our (technological) capabilities? And is the vision of permanent preservation not like a collective ‘control save’ spasm? While writing this essay, the Corona in the City exhibition was suddenly ‘off the air’ – temporarily evaporated. Whereas the vaccination syringe will quite certainly have lain in the museum depot all that time, unperturbed.

***

The question remains exactly what our narrative will be. Is it especially about the beautiful (be sure to visit the gallery ‘Sound of Silence’ showing Amsterdam’s empty nightclubs), or just as much about the ugly? The solidarity, or also the loneliness? How do you collect bankruptcies, sickness and death? Meandering through Corona in the City I came upon a photo of a slogan carried at a demonstration by what was then still called the Viruswaanzin movement, at Museumplein: ‘I so much long to dance and hug again.’ Will our story also accommodate the violence that accompanied the same demonstrations? In fact, it turns out that there’s a whole gallery devoted to this theme, titled ‘Disobedient citizens and protest’.

A cry from the heart, by Suzanne Bunnik

Corona in the City confronts us with a paradox: no single person is able to recount the story of how coronavirus impacted the city, but nor is everyone collectively. Completeness is an illusion, a phantom of all eras, but still one thing has become clear: we need to keep our finger on the pulse of today in order to better write history.

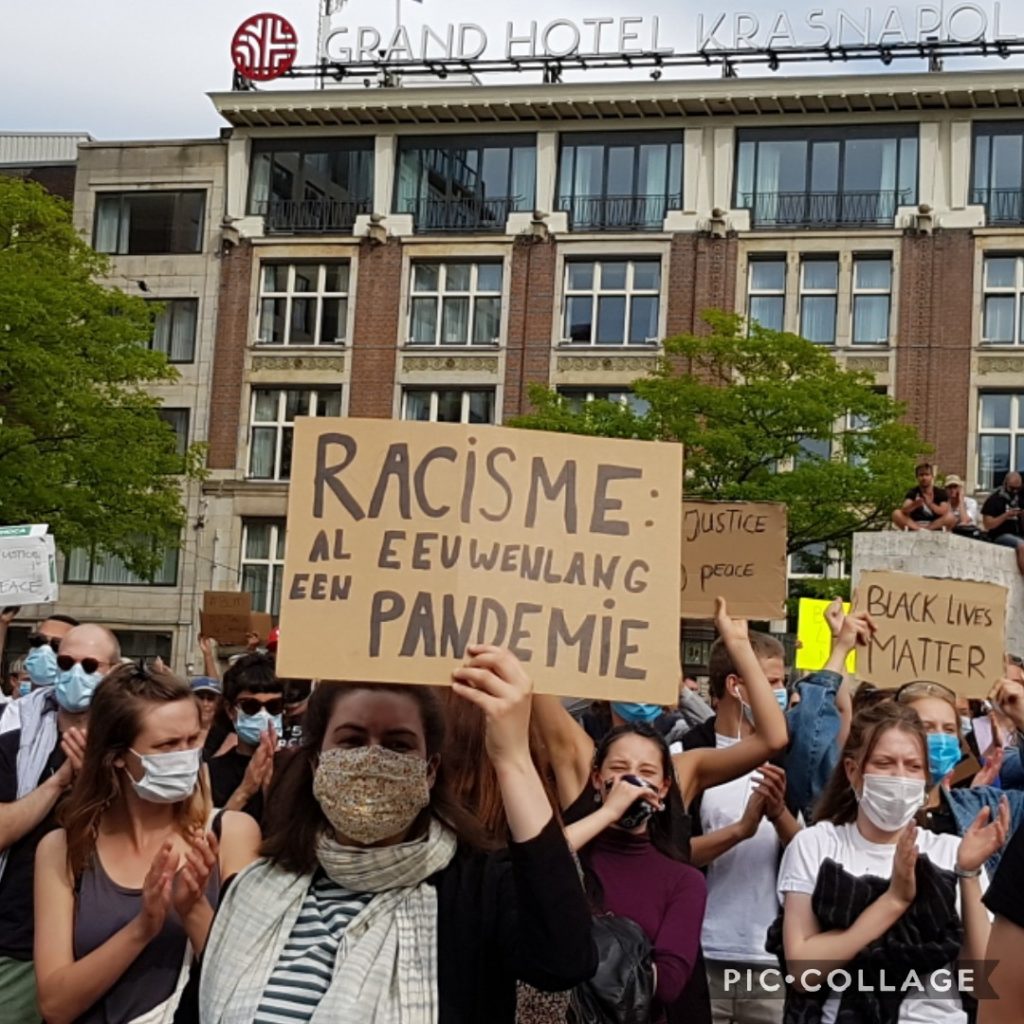

That is what the Amsterdam Museum is doing. Corona in the City’s trump card is the experiment in collecting in real-time. It has immediately yielded valuable items, for the past year wasn’t just the year of corona. For example, the gallery ‘Black & LGBTQIA+: A Timeless Tribute to Us’ depicts the black queer community during the time of corona, and also documents the first-ever Black Pride event in the country. The struggle against racism and the demonstrations of the Black Lives Matter movement have also been compiled in a gallery. Dozens of photographs show the banners and cardboard signs (‘Racism: a centuries-old pandemic’), and stories add what it all meant for the demonstrators personally.

‘Today, 10 June 2020, marked a turning point in my life. That’s what it felt like when I joined thousands of other demonstrators at the Black Lives Matter demonstration in Nelson Mandelapark’, writes Shanti Alfour in his contribution. ‘The Bijlmer suburb gave me a feeling of coming home, and this time I hope I can take that feeling with me wherever I go.’ In a vlog about Keti Koti, the annual Surinamese celebration of the abolition of slavery which, very unfortunately, could not be held in-person this year, a Winti priestess describes how she performs a libation each year at the National Monument to slavery. And there is an open letter to mayor Halsema, written by Massih Hutak on behalf of a group of friends, to thank her for demonstrating solidarity with victims of anti-black violence.

Corona in the City is a living archive in which you can wander around and get lost, and can get bored and be surprised – just as in a real city. As a museum collection, it actually harbours dozens of separate exhibitions. For instance on the theme of intimacy and distance, the individual and the group, or on a new sound in sudden silence. Or about construction and destruction, also literally as with the scenery of the Hamlet performance by Theater De Krakeling, de Toneelmakerij and Theater de Meervaart, which had to be dismantled even before it premiered, while homeless shelters and food banks were being built up elsewhere at the same time.

Dismantling a performance that had yet to premiere, by Theater De Krakeling

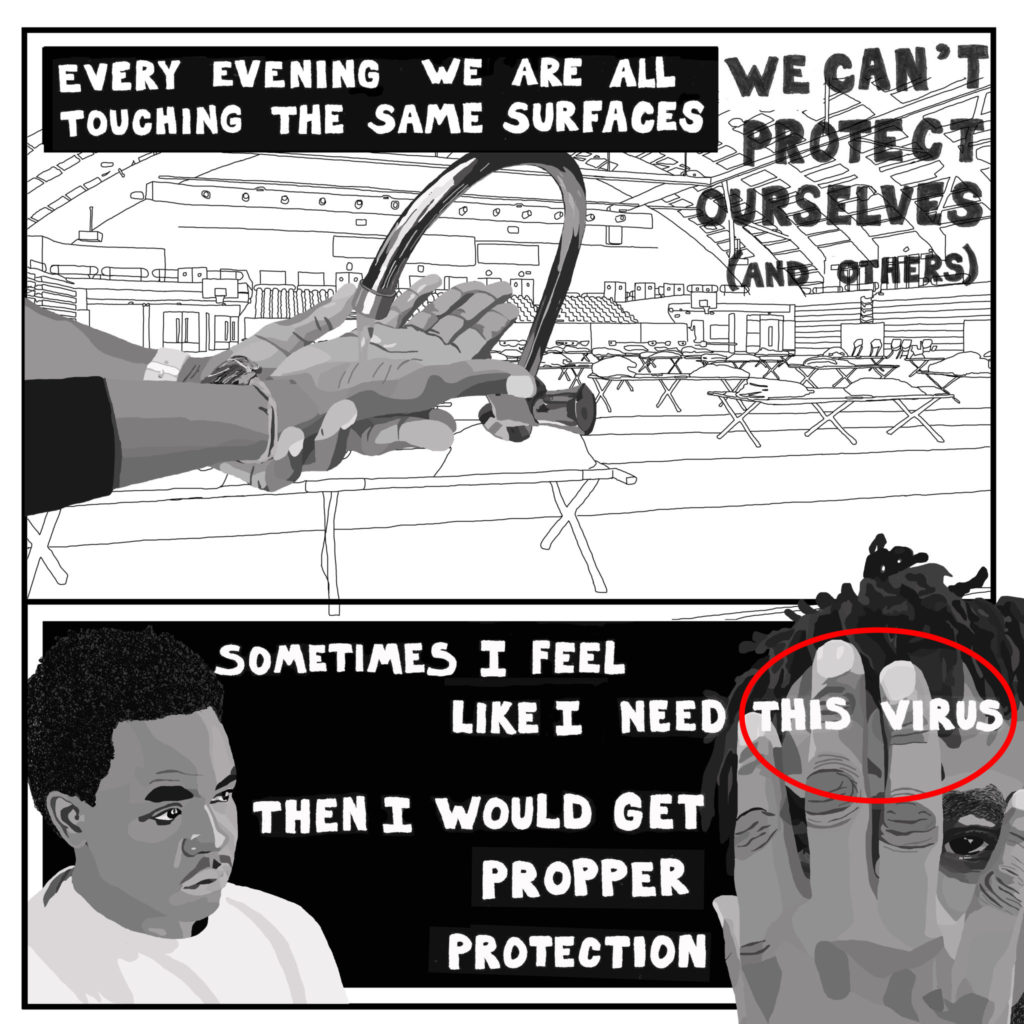

As a diary of the city, the exhibition is a tribute to the citizens who managed to find each other in a new place, or instead lost sight of each other. Homeless Quarantine by the We Sell Reality collective is a series of graphics created in collaboration with ‘refugees in limbo’. While the whole country was instructed to remain indoors, these refugees were forced to live out on the street, in a present-day pandemic and pursued by a political past. These forces fuse together in these vivid images. One of them says: ‘Sometimes I feel like I need this virus. Then I would get propper protection.’

These are the kinds of stories, taking place in our city, that need to be heard now. Will such testimonies be preserved for the future, and if so, what message will they represent then? There’s no way of knowing.

Homeless Quarantine, door We Sell Reality

This article was translated by Jan Warndorff (BeterEngels).